Photo by Slejven Djurakovic on Unsplash

How does a C program run? - An oversimplification, but its all you'll ever need

System design is the backbone of software engineering, and understanding how a program transitions from code to execution is crucial for building efficient and scalable systems. In this blog post, I’ll be kickstarting the System design series, by breaking down the journey of a C program from compilation to execution, exploring the key concepts of memory management, process creation, and CPU execution.

Step 1: Writing and Compiling a C Program

When you write a C program (.c file), it is just human-readable code. The compiler converts it into machine code that a processor can understand.

Compilation Process

The compilation process consists of four main steps:

Preprocessing (

cpp): Handles#include,#define, and macro expansion.Compilation (

gccorcc): Converts preprocessed C code into assembly (.sfile).Assembly (

as): Translates assembly code into machine code (.oobject file).Linking (

ld): Combines object files and libraries into an executable (a.outor named binary).

At this point, the compiled executable is stored on the disk.

Step 2: Loading the Program into Memory (Creating a Process)

When you run the program (./a.out), the OS loads it into RAM and creates a process. This is done by the loader (part of the OS).

Steps in Loading the Program:

Executable File Read: The OS reads the binary executable from the disk.

Memory Allocation: The OS allocates space in RAM for:

Code Segment: Stores the compiled machine code.

Data Segment: Stores global and static variables.

Heap: Stores dynamically allocated memory (

malloc,calloc).Stack: Stores local variables, function calls, and return addresses.

Process Control Block (PCB) Creation: The OS creates a PCB, which tracks the process ID (PID), registers, memory layout, and execution state.

Page Tables Setup: The OS sets up a page table to map virtual addresses to physical RAM locations.

Transfer Control to Entry Point (

main): The CPU sets the instruction pointer (IP) to the entry point (mainfunction), and execution begins.

Step 3: Memory Layout of a Running Process

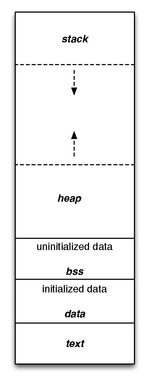

When a process is running, it is structured into several segments:

1. Text (Code) Segment

Contains machine instructions (compiled binary).

Typically read-only to prevent accidental modification.

Loaded from disk into RAM.

2. Data Segment

Stores global and static variables.

Contains:

Initialized Data: Pre-set global/static variables (

int x = 10;).Uninitialized Data (BSS): Global/static variables initialized to zero (

int y;).

3. Heap

Stores dynamically allocated memory (

malloc,calloc,new).Grows upwards in memory as needed.

4. Stack

Stores:

Function call frames (return addresses, local variables).

Arguments passed to functions.

Grows downwards in memory (towards lower addresses).

Managed automatically by the CPU.

Step 4: Execution by the Processor

The CPU executes the program instruction by instruction:

Fetch: The CPU fetches the next instruction from the text segment in RAM.

Decode: The CPU decodes the instruction.

Execute: The instruction is executed (e.g., an arithmetic operation, memory access).

Memory Access: If needed, data is read from or written to RAM.

Write Back: The result is stored back in registers or memory.

Repeat: The cycle continues.

The stack and heap are just areas of RAM managed dynamically as the program runs.

Step 5: Process Termination

When the program ends:

The OS reclaims memory (stack, heap).

The process exits (status code is returned).

The PCB is deleted.

Where Are Processes Stored?

A process is not stored in one fixed location but exists as an entity managed by the OS. However, the main components of a process are:

Executable File on Disk

- Before execution, the program exists as a binary executable file (

a.out,my_program.exe, etc.) on the disk.

- Before execution, the program exists as a binary executable file (

Process in Memory (RAM)

- When executed, the OS loads it into RAM and organizes it into different segments (code, data, stack, heap).

Process Control Block (PCB) in Kernel Space

- The OS maintains metadata about the process (PID, registers, memory layout, state) in a structure called the Process Control Block (PCB), which is stored in kernel space (not user space).

Does Each Process Have Its Own Stack and Heap?

Yes, every process has its own stack and heap.

Stack (for function calls, local variables, return addresses)

Heap (for dynamically allocated memory using

malloc,calloc,new, etc.)

Since processes are isolated from each other (protected by virtual memory), each process has its own separate stack and heap.

Do Both Stack and Heap Reside in RAM?

Yes, both the stack and heap are parts of the process’s memory in RAM.

The stack grows downwards (towards lower addresses).

The heap grows upwards (towards higher addresses).

The OS dynamically manages memory allocation and deallocation.

Process Memory Layout in RAM:

When the CPU Executes Instructions, Is It Reading the Program or the Process?

The CPU executes the process, not the program on disk.

The program (executable file) is a static file stored on disk.

When you run it, the OS loads it into RAM as a process.

The CPU reads instructions from the RAM (text/code segment of the process), not from the disk.

The fetch-decode-execute cycle happens on instructions stored in RAM, meaning the CPU is reading and executing the process, not the original program file on disk.

By understanding these fundamental concepts, you’ll be better equipped to design systems that are efficient and scalable. Whether you're optimizing memory usage or debugging process-related issues, this knowledge will serve as a solid foundation for your journey in system design. Happy coding!